Orange Shirt Day is a day to remember, to witness, and to honour Residential-School survivors, their families, and communities; and to demonstrate a personal and organizational commitment to reconciliation. This year Thursday, September 30 is Orange Shirt Day across Canada.

To support Northern Health’s awareness and understanding of the significance of Orange Shirt Day, the Indigenous Health Department will be sharing information and resources each week throughout September.

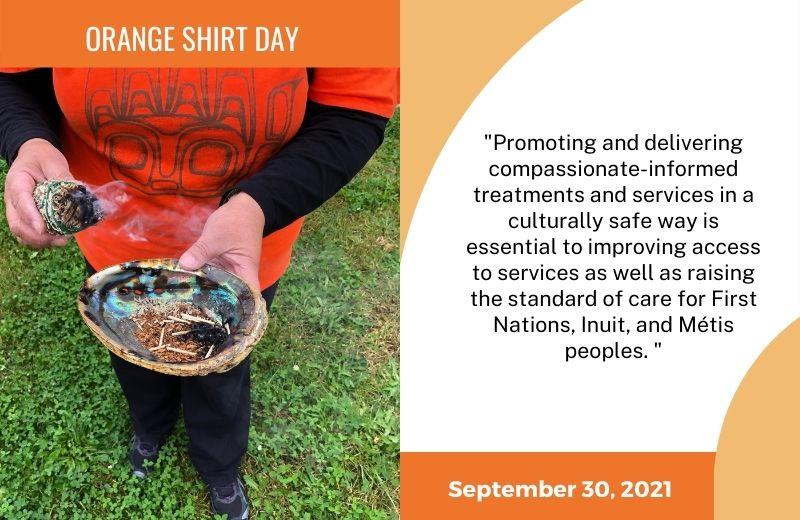

This week we are discussing the importance of trauma-informed and compassionate-informed care for Indigenous peoples.

What is trauma-informed care?

Trauma-informed care is a strengths-based approach to health care that builds on an understanding that an individual’s past and current experiences of trauma can affect their experiences within the medical system, education system, and other systems. There are many forms of trauma, such as:

- Single-incident trauma can include experiencing a serious accident or natural disaster.

- Complex or repetitive trauma can result from abuse, domestic violence, and war.

- Developmental trauma includes damaging childhood experiences such as child abuse and neglect.

- Intergenerational trauma is experienced by people living with others who have experienced trauma in their own lives.

- Historical trauma includes the long-term effects of a social group’s experience of genocide, colonialism, slavery, and war. Historical trauma can deeply affect people for many generations after the traumatic event has occurred.

For Indigenous peoples, historical trauma stems from a violent history of colonization within Canada. Indigenous peoples were forcibly removed from their lands and territories and moved onto reserves. Indigenous children were seized from their families and forcibly placed in residential schools. In addition, many Indigenous people across the country experienced substandard health care, medical experimentation, and multi-year confinement within the Indian hospital system. There were three Indian hospitals across the province of British Columbia. Of these, Miller Bay Indian Hospital was located in the North near Prince Rupert, BC.

Traumatic events like the ones above led to an overall loss of language, tradition, and culture for First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. The effects of these traumatic experiences continue to impact Indigenous peoples’ health and well-being.

To be a trauma-informed health care provider is to have compassion. A compassionate-informed approach can enhance health care service delivery and support respectful relationships across health professions and disciplines.

How can health care professionals incorporate compassionate-informed care into their practice?

The goal of compassionate-informed care is to support people to make decisions about their healthcare and treatment needs in ways that feel safe to them, while avoiding the possibility of their re-traumatization.

Promoting and delivering compassionate-informed treatments and services in a culturally safe way is essential to improving access to services as well as raising the standard of care for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.

Hospitals and doctors’ offices can feel unsafe for someone who has experienced trauma. As health care providers, you can create safe and comfortable environments for people when we actively recognize, acknowledge, and understand that trauma can be present.

A compassionate-informed care approach begins with building professional and staff awareness of:

- The high frequency of traumatic experiences among the general population;

- The impacts of trauma on development over the lifespan;

- The ways in which Indigenous peoples’ health and well-being is directly impacted by the colonial experience;

- Behaviour adjustments individuals make after surviving trauma; and

- The association between trauma and health comorbidities.

When health care professionals build their awareness of these factors and experiences associated with trauma, they’re better able to support an organizational culture of compassion informed care. A compassion informed approach to health care emphasizes a person’s safety, choice, and control over their own care.

What steps is Northern Health taking?

One of the steps NH is taking to advance culturally safe health care is developing the Making it Real: Cultural Safety in Northern Health framework (“the Framework”).

The Framework is a living document for the organization that is designed to be flexible and responsive. The purpose of the Framework is to facilitate health system transformation within NH. The Framework aligns with NH’s Strategic Plan (2021) and elements of the Northern Partnership Accord (2012) including:

- Work with local First Nations people through NH’s Aboriginal/Indigenous Health Improvement Committees (A/IHICs) to improve the quality and cultural safety of NH’s services at the community level.

- Increased understanding and respect for First Nations traditions, customs, and protocols between NH and Northern First Nations.

- Improved access and culturally safe health services for First Nations (Indigenous peoples).

The Framework builds on existing relationships and strengths. Future work will focus on individual, system, and structural activities and initiatives for health system transformation to address systemic racism, including anti-Indigenous racism.

You can also help to improve BC’s health care system by participating in the BC First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Cultural Safety and Humility Standard Public Review. The standard outlines the responsibilities of health systems and organizations in BC to establish a culture of anti-racism and cultural safety and humility in their services and programs, to better respond to the health and wellness priorities of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples and communities they serve. You can learn more about the BC First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Cultural Safety and Humility Standard and participate in the Public Review on the Health Standards Organization (HSO) website. Public feedback will be accepted by the HSO until September 23, 2021.

Additional resources

- Aboriginal peoples and historic trauma

- Decolonizing trauma work: Indigenous stories and strategies

- Healing families, helping systems: A trauma-informed practice guide for working with children, youth, and families

- Trauma-informed care champions: From treaters to healers - A series of videos for health care providers

- Trauma-informed practice guide

Support available

Support is available for anyone affected by the residential school experience.

- A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.

- The KUU-US Crisis Line Society provides a First Nations and Indigenous specific crisis line available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, toll-free from anywhere in British Columbia. The KUU-US Crisis Line can be reached toll-free at 1-800-588-8717 or online.

- The Northern BC Crisis Line offers 24/7 support across the NH region, and can be reached at 1-888-562-1214.

Comments